by Renée J. Lukas

by Renée J. Lukas

In Screenwriting 101, you learn about the inciting incident, hopefully occurring in the first act of your screenplay. This is the moment where the protagonist can never return to who she was before. Something has changed the protagonist forever.

You can’t underestimate the importance of the inciting incident. If you do, script readers may wonder “Why should I care?” That spells death for your script AND your chances of getting it sold.

So, when crafting your inciting incident, think big. How big can the stakes get?

The Key to a Good Inciting Incident

Remember, most people follow the path of least resistance. Let that sink in. Sure, we’d all like to think of ourselves as heroes, doers, movers and shakers. . .but the reality is the opposite. You yourself probably wouldn’t change your daily routine unless some major event forced you to, like a meteor slamming into your house.

If you were Luke Skywalker in Star Wars – Episode IV – A New Hope, you’d probably be content to be a space mechanic on Tatooine—especially if it’s a good job, nice 401k. . . Why would you, all of a sudden, leave the familiar surroundings of home to take on the darkest, deadliest forces in the universe, risking certain death?

The answer is, you wouldn’t.

Unless that dark force murders the only family you’ve ever known, upending your comfortable, safe existence, only then, you might consider leaving for a mission greater than yourself.

How to Write an Inciting Incident

Think of your main character. Then decide what it would take to pull her out of her comfort zone. If you’re not writing an epic saga about good versus evil across the universe, think of it this way: your characters may not be saving the world, but the inciting incident has to mean something big to them, such as:

- The moment Andy’s co-workers find out that he is, in fact, The 40-Year-Old Virgin. Life was just fine for Andy before he suffered that humiliation. Now things are going to go in a very different direction!

- When Elle is dumped by her true love because he doesn’t think she’s smart enough in Legally Blonde. This sets the stage for all the actions Elle takes from that point on, actions she never would have considered otherwise.

- In Under the Tuscan Sun, Frances suffers the biggest blow—not only learning of her husband’s affair, but also having to leave the house she bought. If it weren’t for that, she would never have gotten on that plane to Italy!

Inciting Incidents from Dramas

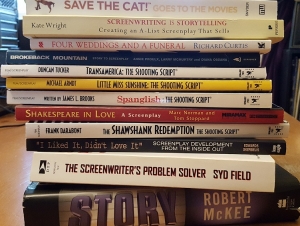

- When Andy Dufresne is convicted of murdering his wife and her lover and sentenced to life in prison in The Shawshank Redemption.

- When Skeeter reaches out to Aibileen to get “her side” of the story in dangerous 1960s Mississippi, putting both of them at great risk in The Help.

- When Jim wakes up and realizes he’s the only one whose sleep pod malfunctioned and he’s awakened 90 years too early in Passengers.

Keep thinking about what will force your characters out of the path of least resistance throughout the story, no matter which act you’re writing. For example, in The Help, it would have made no sense for hundreds of African-American maids to suddenly, eagerly tell their stories about working for white families. With the backdrop of segregation, random police searches and murder, it would only be plausible for the maids to reach a point where they feel compelled with rage, and / or have nothing else left to lose before agreeing to participate in something so dangerous.

The Problem with Writing Heroes

Many writers like to write about “heroes.” I’ve put that in quotes because it’s more of an idea than a reality. If your hero starts out as an unbelievable risk-taker who puts others before himself, he’ll be a tough character to relate to. Think about your own life. What are you willing to give up? What would it take for you to even consider putting your own life on the line? Whenever someone is writing about a “hero,” they need to dig deeper and find out what made this person who they are, and it has to be something believable.

The movies are often a fantasy land that stretches the truth and the imagination. But the best movies stay true to the principles of human nature. Base your inciting incident on a plausible no-other-way-out scenario, and the audience will more willingly go along for the ride with you.